|

| Book cover: The Popish Midwife |

|

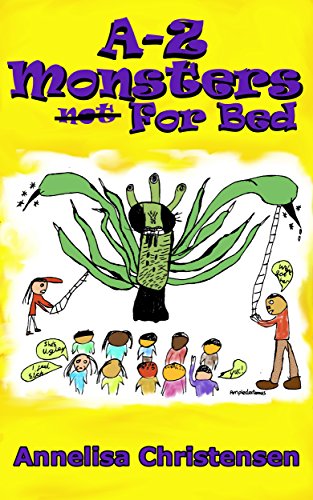

| Book cover: A-Z Monsters (not) For Bed |

See? No connection.

Or is there...?

Of course there is. You knew that. Otherwise why would I be telling you all about it! :-D

So, what's the connection? It's rhyme. Allow me to share the tie with you...

During my time researching The Popish Midwife, one of the things I most enjoyed was the seventeenth century coffee house and broadsheet satire, which made comment on anything and everything at the time. Nothing was sacred. Coffee houses and Taverns were the hotbeds of community news everyone slept in on a regular basis. There, amongst the smoke rising from clay pipes and burning rushlights or candles on the wall, could be read leaflets, broadsheets and newspapers about current affairs; and imbibers of dishes of coffee or cups of ale could catch up with gossip along with all the other regulars.

|

| Elizabeth mentioned in "A Message from Tory-Land" |

I found out so much about Elizabeth Cellier through broadsheets and leaflets of satire and jolly rhymes, which I fondly imagine the writer having a riot of a time creating, laughing and guffawing over as he came up with each new idea and line, making the reading of long passages so much more fun and entertaining because, of course, news was openly considered entertainment back then. The wittier the better. Even life-and-death stuff, which is obviously very serious, was given a dash of hilarity to it. It helped to deal with the much harsher life events in a way that the living could feel comfortable with.

For instance, from the broadsheet A Message from Tory-Land (above left), there is information spilling out of every single verse, and covering religion, politics, murder, trials [Verse 7 is dedicated to Elizabeth Cellier]:

[7]

But dear Madam Celiers intrigue did miscarry,

You see that 'tis dangerous to be unwary,

these Hereticks must by all means be destroyed,

And all the Church Rights by us be injoyed,

Yet if we arm us, ram us, damn us

these Heretick Dogs will find Ignoramus,

Still it miscarries, it tarries, it varies,

Yet never were days so blest as Queen Maries.

[note: Queen Maries = Queen Mary's]

and here's another:

The author of Satire Upon the Jesuits (below right) definitely doesn't have such a fine tuned sense of rhythm and rhyme as the author of A Message from Tory-Land, but he (or maybe, in secret, a she) certainly can ridicule and insult along with the best of them. He derides Catholic ceremonies of taking communion, casts aspersions on the priests, reflects popular opinion that Cellier, being a midwife, is as great a bawd, a whore, as all other midwives. That he brought her in to this verse is comment on how infamously she was tied to the fate of the Jesuits on trial and to the Popish Plot. [The lines re Cellier are highlighted by me.]

|

| Elizabeth Cellier mentioned in "Satire upon the Jesuits" |

'Presto begone!' 'Tis now a deity.

Two grains of dough, with cross, and stamp of priest,

And five small words pronounced, make up their Christ.

To this they all fall down, this all adore,

And straight devour, what they adored before-

'Tis this that does the astonished rout amuse,

And reverence to shaven crown infuse,

To see a silly, sinful, mortal wight

His Maker make, create he infinite.

None boggles at the impossibility;

Alas, 'tis wondrous heavenly mystery!-

And here I might (if I but durst reveal

What pranks are played in the confessional:

How haunted virgins have been dispossessed,

And devils were cast out, to let in priest:

What fathers act with novices alone,

And what to punks in shrieving seats is done,

Who thither flock to ghostly confessor,

To clear old debts, and tick with Heaven for more.

Oft have I seen these hallowed altars strained

With rapes, those pews which infamies profaned;

Not great Cellier,* nor any greater bawd,

Of note, and long experience in the trade,

Has more, and fouler scenes of lust surveyed.

But I these dangerous truths forbear to tell,

For fear I should the Inquisition feel.

Shoud I teall all their countless knaveries,

Their cheats, and sams, and forgeries, and lies,

Their cringings, crossings, censings, sprinklings, chrisms,

Their conjurings, and spells, and exorcisms,

Their motley habits, maniples, and stoles,

Albs, ammits, rochets, chimers, hoods, and cowls;

So much commentary, so many oft-spoken opinions; one can't ask for a more thorough summary and condensed view of the emotion and reaction of the the society. This richness made it so much easier to understand the different aspects of the seventeenth century society.

We politically- and socially-correct people of today might have great trouble laughing at other folks' misfortunes in this way (and would probably get sued if we did!). Even to elude to something being funny, for instance, that certain politicians in the highest places might be double-dealing or siding with the enemy to the risk of the country, might elicit a strong reaction. Laughing about it would be seen as expressing that it's of no consequence, belittles it in many a person's eyes. It could be considered a tad too frivolous. Such serious subjects should be discussed and and thought about with gravity and solemnity... unless, of course, you're a stand-up comedian. And even then, there are those who would take offence at your making merry over a serious matter.

Centuries ago, the way it was told and passed on was paramount. If it wasn't told with horror and excitement, it should be told with humour and memorable words if the news was to spread far. I expect those good at making up these broadsheet rhymes would probably have built quite a reputation for themselves, and possibly even been employed to write with the sole intention of getting the subject matter throughout the kingdom. Word of mouth wasn't quite as widespread as previous centuries, but it was still strongly relied on. Even more so in ancient times...

Going back centuries before, to the Ancient Greeks and probably earlier, famous poetry, like the Iliad and Odyssey, were also written in verse, the tempo of which is kept moving by the short lines, and the names and events made memorable by repetition of description (twenty five-twenty six thousand of them! If I were to write a similarly long verse about Elizabeth Cellier, for instance, I might always call her 'the bold and brassy midwife', and that exact expression would be used each and every time mentioning her.). There was a reason for this. Back in the days when not everything was written down, and long stories were told by oration, there had to be easier ways for the storyteller to remember it all. Yes, some details changed each time of the telling, but most of it was remembered in chunks of ideas. When Alexander Pope translated The Iliad in the early eighteenth century, he used heroic couplets. Why? Not only because they were all the rage during the Restoration, but also they are very pleasing to the ear, and memorable.

In the way songs are. In fact, back then, many stories were sung to music by travelling story tellers.

So, this is where I come back to A-Z Monsters for Bed, which I wrote in a concentrated poetry-writing period almost two decades ago. I was going through some difficult life-stuff at the time, much like now, and I found that writing humorous story rhymes were not only good at focusing the mind, but they also entertained me while I wrote them. Twenty six rhymes reflecting upon, and animating through story, various traits and characteristics that might be considered bad/monstrous (many of the monsters have such names as Scurulous, Cantankerous, Xenophobia). Only one - Quantum Querulous - was not a full story but a short limerick/riddle. I found the high concentration of rich language was wonderful to play with, and a story that might have taken a thousand words could be reduced to a fraction of that, to maybe one or two sides of A4.

But, most of all, I found one could conjure sharp images with a well-chosen line, a twist of word order, an evocation of a whole idea encompassed in a phrase, and the rhyme-ends helped to keep together ideas. Re-reading those rhymes, I understood how pleasing they are to write, how enjoyable and animated they are to read. For instance, a few years later, my young niece enjoyed one of the story-rhymes so much, she learned it by heart to recite at school (apparently it went down well). When I was working in my son's school, I read some of the rhymes to the ten-year-olds, and they loved them. I mean, really loved them. They were engrossed and smiling, and remembered particular bits of them afterwards. To me, this is an indication of how much easier and more fun it is to learn in such a way, and I can't help thinking what a shame it is that rhymes as a form of poetry, and rhyming stories in particular, have gone so out of fashion.I believe that kids these days might find them refreshing.

I know there are still many authors that do write children's rhyming books, but it seems to be mostly for the very young. What about the older children and adults who would get so much out of the funny verses? I decided, I'm going to bring rhyming back. Ok, not on my own, but I'll start by writing more of it (I'm working on a book of Halloween story-rhymes I hope to release for Halloween 2017). And I will discover as many works of this art as I can, and share them with all who are interested on a separate page of this blog. I hope to encourage in you, the older reader, a re-discovery of the fun of rhymes too. If you do, please share with me in the comments below, and share with everyone else you can:

Bring Back Rhyming!

The other bonus, by the way, is that in this time-focused society, where we are all overwhelmed with the many things we should do, and have to-do lists growing out of our finger tips onto many pages (mentally or otherwise), so we never feel we have time for anything, the shorter story-rhyme is a perfect solution to give you a giggle during your coffee break, or share reading with your child later...

Finally, I'll leave you with a rhyme for the coronation of King William III (William of Orange) and Queen Mary when King James II escaped to France in 1689. I hope you can read it.